The Seattle Post Intelligencer

Saturday, October 27, 1984

Section C—Entertainment C/4

A mansion-sized task

Old home now basks in its former elegance

Don Carter, P-I Reporter

Forty-eight years ago Sanford Wright, Sr., had an argument with former Governor Roland Hartley. Wright, a general contractor, had been hired to replace the rotting porch railings on Hartley’s elegant Everett mansion. Wright proposed to duplicate the original turned-wood balusters and preserve the mansion’s appearance, but “he (Hartley) thought that would cost too much money…I had to do it with two-by-fours,” the retired contractor recalls, grimacing at the architectural travesty.

Last summer, Wright returned to the historic 73-year-old mansion to do the job the way he wanted to do it in 1936—for his son, the new owner, who was not only agreeable but insistent on restoring the mansion to its original appearance.

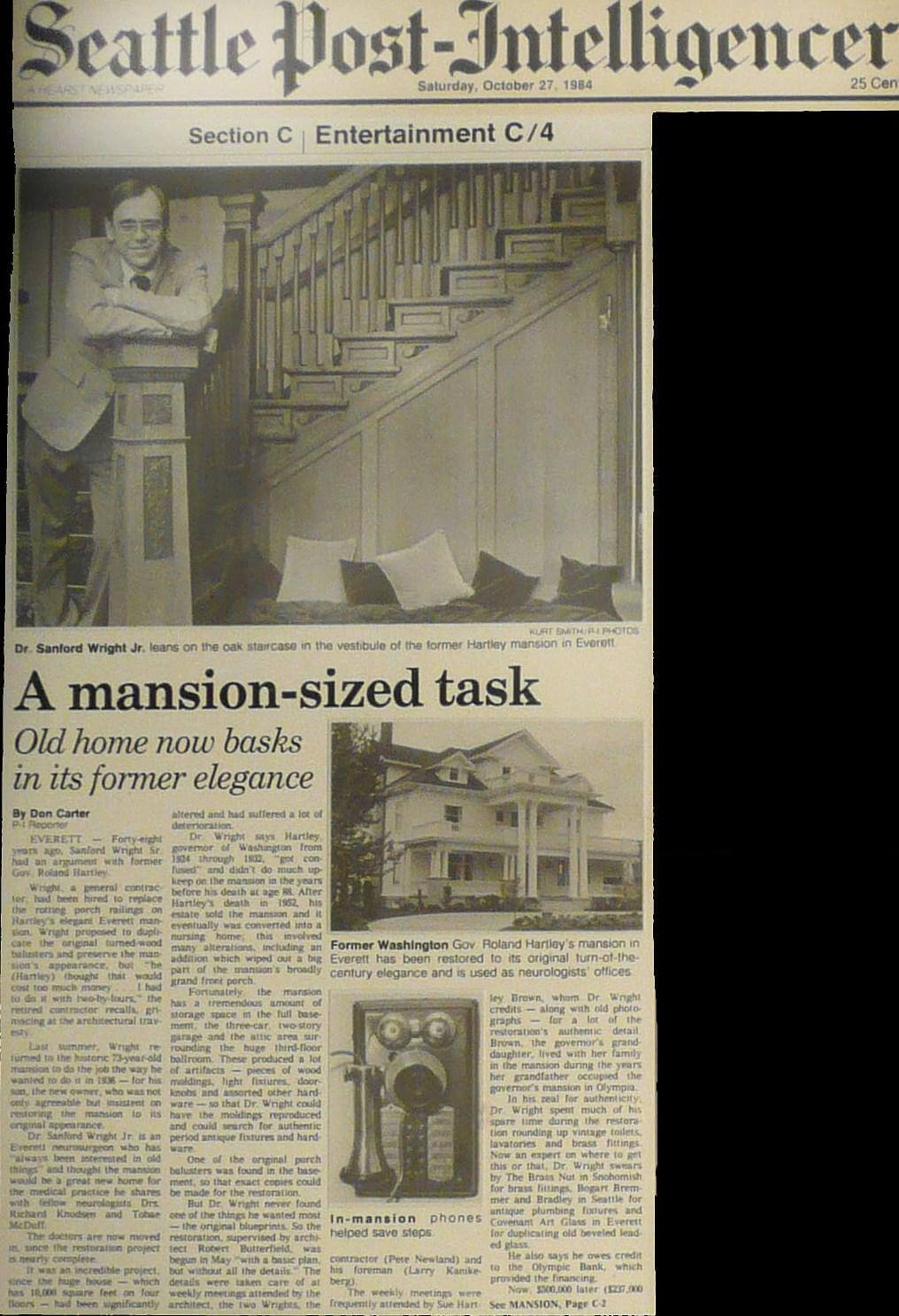

Dr. Sanford Wright, Jr., is an Everett neurosurgeon, who has “always been interested in old things” and thought the mansion would be a great new home for the medical practice he shares with fellow neurologists, Drs. Richard Knudsen and Tobae McDuff.

The doctors are now moved in since the restoration project is nearly complete.

It was an incredible project, since the huge house, which has 10,000 square feet on four floors, has been significantly altered and had suffered a lot of deterioration.

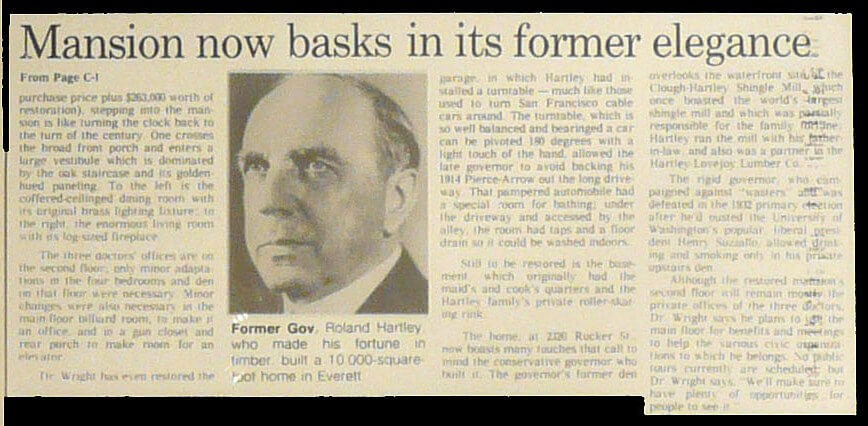

Dr. Wright says Hartley, governor of Washington from 1924 through 1932, “got confused” and didn’t do much upkeep on the mansion in the years before his death at age 88. After Hartley’s death in 1952, his estate sold the mansion, and it eventually was converted into a nursing home; this involved many alterations, including an addition that wiped out a big part of the mansion’s broadly grand front porch.

Fortunately, the mansion has a tremendous amount of storage space in the full basement, the three-car, two-story garage, and the attic area surrounding the huge third floor ballroom. These produced a lot of artifacts—wood moldings, light fixtures, doorknobs, and assorted other hardware—so that Dr. Wright could have the moldings reproduced and could search for authentic period antique fixtures and hardware.

One of the original porch balusters was found in the basement, so that exact copies could be made for the restoration.

Dr. Wright never found one of the things he wanted most—the original blueprints. So the restoration, supervised by architect, Robert Butterfield, was begun in May “with a basic plan but without all the details. The details were taken care of at weekly meetings attended by the architect, the two Wrights, the contractor (Pete Newland), and his foreman (Larry Kanikeberg).

The weekly meetings were frequently attended by Sue Hartley Brown, whom Dr. Wright credits—along with old photographs—for a lot of the restoration’s authentic detail. Brown, the governor’s granddaughter, lived with her family in the mansion during the years her grandfather occupied the governor’s mansion in Olympia.

In his zeal for authenticity, Dr. Wright spent much of his spare time during the restoration rounding up vintage toilets, lavatories, and brass fittings. Now an expert where to get this or that, Dr. Wright swears by The Brass Nut in Snohomish for brass fittings, Bogart, Bremmer, and Bradley in Seattle for antique plumbing fixtures, and the Covenant Art Glass in Everett for duplicating old beveled leaded glass.

He also says he owes credit to the Olympic Bank, which provided the financing.

Now, $5000 later ($237,000 purchase price plus $263,000 worth of restoration), stepping into the mansion is like turning the clock back to the turn of the century. One crosses the broad front porch and enters a large vestibule which is dominated by the oak staircase and its golden-hued paneling. To the left is a coffered-ceilinged dining room with its original brass lighting fixture; to the right, the enormous living room with its log-sized fireplace.

The three doctors’ offices are on the second floor; only minor adaptations in the four bedrooms and den on that floor were necessary. Minor changes were also necessary in the main-floor billiard room, o make it an office, and in a gun closet and rear porch to make room for an elevator.

Dr. Wright has even restored the garage, in which Hartley had installed a turntable—much like those used to turn San Francisco cablecars around. The turntable, which is so well balanced and bearinged, a car can be pivoted 180 degrees with a light touch of the hand, allowed the late governor to avoid backing his 1914 Pierce-Arrow out the long driveway. That pampered automobile had a special room for bathing; under the driveway and accessed by the alley, the room had taps and a floor drain so it could be washed indoors.

Still to be restored is the basement, which originally had the maid’s and cook’s quarters and the Hartley family’s private roller skating rink. The home, at 2320 Rucker Street, now boasts many touches that call to mind the conservative governor who built it. The governor’s former den overlooks the waterfront site of the Clough-Hartley Shingle Mill, which once boasted the world’s largest shingle mill and which was partially responsible for the family fortune; Harley ran the mill with his father-in-law, also a partner in the Hartley-Lovejoy Lumber Company.

The rigid governor, who campaigned against “wasters” and was defeated in the 1932 primarily election after he’d ousted the University of Washington’s popular, liberal president, Henry Suzzalo, allowed drinking and smoking only in his private upstairs den.

Although the restored mansion’s second floor will remain mostly the private offices of the three doctors, Dr. Wright says he plans to use the main floor for benefits and meetings to help the various civic organizations to which he belongs. No public tours currently are scheduled, but Dr. Wright says, “We’ll make sure to have plenty of opportunities for people to see it.”